His presence in the world would have seismic consequences for his time. His wife would secure a reputation as one of the most beautiful women in history, and his son who briefly succeeded him as an obscure and ineffectual ruler would, by a strange twist of fate, become one of the best-known names ever.

For three thousand undisturbed years the Ancient Egyptians had worshiped their many gods and goddesses, and the pattern of their lives and religious beliefs had continued unchanged from one generation to the next. And for those three millennia the two cities of Thebes in [1]Upper Egypt, and Memphis in Lower Egypt, were their sacred capitals. In those many centuries nothing really changed during what was probably the longest-lasting period of constancy in human history. And then the pharaoh Amenhotep IV came to the throne.

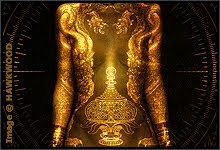

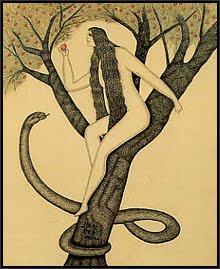

Just six years into Amenhotep's reign, something happened. This pharaoh, who otherwise was supposed to be the servant and representative of the gods on earth, grasped history in his hands and moulded and shaped it into a new form. This form was so radical, so heretical, that it needed a new name to define it. The name which the pharaoh coined was Aten, the one true god, the invisible presence who had created all, and from whom all life flowed. The [2]visible manifestation of Aten was the life-giving sun itself: the golden sky disk which shed its rays like a blessing on the world below. The pharaoh, now the servant of this divine oneness, sealed this recognition of his servitude by changing his name to Akhenaten – Spirit Of Aten. But things did not stop there.

[3]redundant, and in so doing had undercut their own power base in a way that would cast long shadows into his future dreams and plans.

|

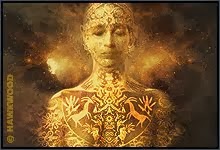

| The pharaoh Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten and initiated a one-man cultural and religious revolution. |

[3]redundant, and in so doing had undercut their own power base in a way that would cast long shadows into his future dreams and plans.

|

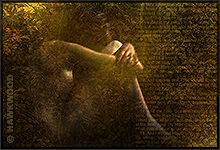

| Blessed by the glorious rays of Aten, the pharaoh and his consort relax with three of their daughters. Such an informal family scene was unprecedented in the art of Ancient Egypt. |

The astonishing one-man revolution continued, with Akhenaten now turning his attention to artistic traditions. Rigid rules of proportion and conventional standards of royal portraiture were abandoned in favour of a daring new realism. To our eyes this new style might not at first appear to be so markedly different from what had gone before, but for its time it was extreme, even shocking. Perhaps the most shocking is the appearance of the pharaoh himself. The expression on the royal face is certainly imperious enough; but with its full lips, broad hips, waspish waist, and suggestion of breasts and rounded stomach, the figure is almost female. So extreme is the exaggeration that it is thought that, if this is indeed a faithful physical portrayal, the pharaoh could have been suffering from Marfan syndrome or Antley-Bixler syndrome: conditions which can produce the elongated limbs and skull deformities suggested by his portraits.

Akhenaten and Nefertiti had six daughters, and even these appear to have had their own remarkable physical characteristic: all of them are shown with a strangely elongated skull. We are left to wonder whether this was a new artistic convention, or whether this as well was an accurate portrayal of some physical deformation, and that the elongated headdresses of their parents actually concealed more than they revealed.

But the pharaoh had one son by a lesser consort, [4]Kiya. This son, whom he called Tutankhaten – The Living Image Of Aten – also appears to have had the same elongated skull as his daughters, and it was this son who would succeed his father to the throne. Like his father, this son also would undergo a change of name, and this change tells its own story. We famously know the son as [5]Tutankhamen. He had a brief reign of just eleven years, dying mysteriously before reaching his twentieth year. The extraordinary revolution in culture and religion which his father had initiated proved impossible to sustain. Following Akhenaten’s death the priests of the old gods seized their chance and moved in to reinstate both the gods and themselves. The glorious architecture of Amarna was ransacked to create their temples anew, and the likenesses of its king and queen were defaced or removed from their pedestals.

Tutankhamen’s name embodies the reinstatement of the god Amen and his pantheon. Cloistered in his palace, accompanied by his radiant queen, and surrounded by sumptuous art, his father had spent more time preoccupied with introducing a new religion and its culture than he had with actually consolidating what he had created. Following Akhenaten’s death, there was in Amarna no power base left to continue the worship of Aten, and every religion needs a power base of some kind to sustain it. And as we know, the strange twist of fate that in the 20th-century saw the discovery of Tutankhamen’s intact tomb with its priceless treasures is what rescued the boy pharaoh from what otherwise would have been an indifferent obscurity.

But the revolution initiated by Akhenaten was not in vain, despite what at first appears to be its failure to sustain itself. A heresy is only viewed as a heresy because it is not an approved majority view, not because it is ‘wrong’. The pharaoh’s heretically extreme idea of a single supreme deity endured. Within decades of the pharaoh’s death another Egyptian would take up the idea and spread it to a new territory and a new culture, and this time it would take root. It is more than coincidence that names such as Moses and [6]Thutmoses are so similar, and that we end each and every prayer with the muttered word ‘Amen’. But that, as they say, is another story.

Names may change, but Akhenaten’s radical and heretical idea of a single formless creative deity has endured. And a certain poetic justice also endures: even with all his great and radical vision, Akhenaten never could have imagined that his [7]'Hymn to the Sun', which in its devotional beauty has been compared to scripture's Psalm 104, would be hauntingly set to music by contemporary American composer Philip Glass and live again - almost three and a half thousand years after the heretic pharaoh had composed it.

Hawkwood

Notes:

[1] The terms 'upper' and 'lower' refer to the distance from the river's source, so Lower Egypt was actually closer to the Nile delta in the north than Upper Egypt in the south.

[2] It is simplistic to think that Akhenaten actually believed that the physical sun was the god Aten. The sun was merely the material manifestation of the formless deity behind it: an idea which also surfaces in my previous post 666: The Number of the Beast.

[3] Akhenaten might also have been driven by political expediency as much as by sincere belief. His father, Amenhotep III, was already disturbed by the growing power of the priesthood. Akhenaten's sidelining of the old gods and their priestly servants also could have been an attempt to curtail this potential threat to the throne of the pharaoh. If that is so, then events showed that he made his move too late, and fatally opted to pursue a course of self-absorbed artistic flowering rather than military backup.

[4] Recent DNA tests conclusively establish that a mummy known only as the Younger Lady found in the Valley of the Kings is the mother of Tutankhamen, but the identity of this mummy is speculative. DNA establishes that the mummy is Akhenaten’s sister, which might or might not mean that it is Kiya. Other possible identities include Akhenaten’s daughter Meritaten, and even Nefertiti herself. While incest was the order of the day at the court of Dynastic Egypt, it also makes DNA conclusions more speculative.

[5] Also written as Tutankhamun and Tutankhamon. Being essentially pictographs, Egyptian hieroglyphs do not express vowel sounds, so converting hieroglyphs into a contemporary written language involves multiple choices and compromise. Placing an ‘e’ between consonants has however become a preferred archaeological protocol, which is why I have opted for ‘Tutankhamen’ and ‘Thutmoses’ in this post.

Sources:

Irwin M. Braverman, MD; Donald B. Redford, PhD; and Philip A. Mackowiak, MD, MBA: Akhenaten and the Strange Physiques of Egypt's 18th Dynasty. Pub. American College of Physicians, 21 April, 2000.

Eliot G. Smith: The Royal Mummies. Duckworth Publishers, 2000.

Reconstructed head of Tutankhamen by forensic sculptor Elisabeth Daynhs for National Geographic magazine, June 2005. Tutankhamen skull scan: CT Scanning equipment by Siemens AG; Data courtesy, the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Arab Republic of Egypt; National Geographic magazine, June 2005. Akhenaten and Nefertiti hands photo by Bryan Jones.

Paul Docherty has created an excellent virtual reconstruction of Akhenaten's sacred capital at Amarna3D.

The Google Earth coordinates for the site of Akhetaten at Amarna are: 27°38’42.78”N 30°53’48.24”E.

The Google Earth coordinates for the site of Akhetaten at Amarna are: 27°38’42.78”N 30°53’48.24”E.

always wondered if this was jewish rule. the promotion of such deformed body types and being a radical in 'monotheism' .. just a thought.

ReplyDelete